Embarrassment at Castine

Embarrassment at Castineby Bob Bernstein

(originally published in Offshore magazine)

As a diver and amateur treasure hunter, I've always been fascinated by Maine's maritime history, particularly as it relates to things that have filled with water and sunk. But in 1982, my interest took a more pro-active turn when I decided to open a dive boat business. Suddenly I needed wreck sites for my customers. Working from the deck of a 30' lobsterboat, my friend, Carl, and I started hunting the mid-coast area from Islesboro to Damariscove Island off Boothbay Harbor. Lo and behold, we located eight sunken ships dating from the turn of the century to the mid-fifties.

It sounds like we accomplished quite a bit, but actually it wasn't that difficult a task. Maine's coastline is peppered with thousands of islands and countless numbers of underwater hazards. Truth is before NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard started marking things, this was not the safest place in the world to explore. Captains lost their boats left and right to Maine's ledges and shoals, and some say there are over 3,000 shipwrecks here.

Maine's Most Infamous Wrecks

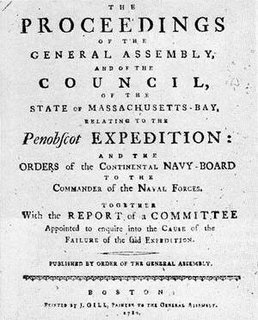

It was not one of our Country's proudest moments. In fact, it cost two Americans their commissions and honor and sent twenty-nine ships and 500 men to their graves. Paul Revere -- considered by so many to be a hero of the revolution -- was court-martialed as a result.

I'm talking, of course, about the battle of Castine, where, in 1779, a fleet of American warships, 39 in all, disgraced the flag and their compatriots while trying to take Fort George from the British. Here's what happened:

Six American navy ships, 13 privateers, and 20 troop transports -- with over 1200 men -- set sail from Boston in July of 1779. They arrived in Castine to find the fort guarded by three British warships and about 500 troops. For some unexplained reason, the Commander of the American fleet, Captain Dudley Saltonstall, chose not to attack with his ships. Instead, he put his troops ashore and laid siege to the castle from land. The battle lasted 21 days, after which the Americans were repulsed and forced to retreat back to their boats.

Not soon after the American troops boarded their vessels, a British officer. Sir George Collier, arrived with six of His Majesty's warships. The British vessels entered the bay from the south and apparently their appearance placed Saltonstall and his officers in such a state that the American commanders ordered their warships to break ranks and flee to the north. When Collier saw the transports abandoned and left drifting, he began to open fire on them with his cannons.

But the disgrace of Saltonstall's opening action was just the beginning. As some of the transports came to rest along the banks, troop commander General Peleg Wadsworth gave orders to set up a line of defense along the river's edge, presumably to provide cover for the fleeing American warships. His artillery officer was none other than the renowned arms maker, silversmith and metalworker, Paul Revere. Ironically, Wadsworth's grandson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, would later immortalize Revere in a poem. But on this day, in July of 1779, Revere proved himself unworthy of such accolades. In violation of Wadsworth's instructions, he scuttled his artillery and munitions into the sea and began a forced march with his men back to Boston.

Meanwhile, Saltonstall and his other captains tried to sail their vessels out of reach of the British Navy. The majority went up river. One, the Defence, tried to make its way to sea. None succeeded in eluding their pursuers, and all were scuttled and burned by order of their commanding officers.

Pickled by Nature, Preserved by Man

Ten years ago, a friend and I dove on two vessels that had been under Penobscot Bay for 100 years. One of the vessels, a 212' three-masted schooner, stood square on its keel as if she had filled with water while on her mooring. Her masts had fallen down, her deck house was gone, and the bowsprit had broken in half, but everything else was in remarkably good condition.

My dive buddy went inside first. With visibility down to a foot or less, he swam carefully through the deck opening and down a set of steps. Inching his way forward, he made his way to the galley. First there was an iron cook stove, then, next to the stove, a crockery jug. Finally, right next to the jug, standing upright as if someone had just put it there . . . a half-full bottle of cooking sherry. All this in a ship that had sunk at the turn of the century.

Scientists believe that a combination of certain sediments, low salt content, still waters, and an absence of wood-eating marine organisms, help keep shipwrecks intact. The wreck my friend and I visited certainly bears this out, but so does another more important find, the wreck of the Defence, discovered by archeologists in the early seventies in a cove in Stockton Springs.

The Defence -- the ship that tried to escape to seaward but eventually got torched by her captain, John Edmonds -- was partially salvaged by a team of scientists working for the State. While some of her artifacts were preserved and placed on permanent display at the museum, the bulk of her lies on the bottom. In fact, because saving sunken treasure for all eternity is such a time-consuming and expensive process, the State decided to leave most of what they found right where it was. They brought stuff to the surface, photographed it, cataloged it, put it in a big net, then gave it back to the sea. Why? Because the Upper Penobscot Bay is the perfect pickle jar.

Paul Revere's Silver Collection

I've toyed with the idea of searching for Paul Revere's treasure ever since that day my friend and I found that half-full bottle of cooking sherry. My interest is further peaked whenever I visit the Defence exhibit in Augusta. But there are three reasons my salvager's sea bag remains empty: (1) Silver doesn't have the staying power of gold, a remarkably everlasting metal; whereas the Penobscot River and Upper Bay are the perfect pickle jar, silver is not the perfect pickle; it doesn't take much to destroy any or all of its filigree, and it has a very low resistance to surface corrosion. (2) The State has laws that prohibit private citizens from removing historical artifacts from State waters, and (3) Revere's collection supposedly went down on the Spring Bird -- scuttled and burned somewhere north of Hampden.

Hampden's just south of Bangor, but way, way, way upriver. This means the person who succeeds in finding Revere's sunken treasure will have to dig through over 200 years of accumulated sediment. The ship might be under 50' of mud and silt. Or maybe the captain and crew of the Spring Bird removed the treasure, carried it inland, and buried it somewhere between here and Boston. Perhaps they stole it from Revere and divided it between themselves. Or maybe Revere came back to Maine and dug it up himself. Nobody knows for sure.

There are at least two certainties though: History remembers Revere for his ride through the Commonwealth and not for his cowardice or insubordination at the battle of Castine. For all intents and purposes, people seem to prefer it that way.

-seabgb

Copyright © Bob G. Bernstein (seabgb) All Rights Reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment